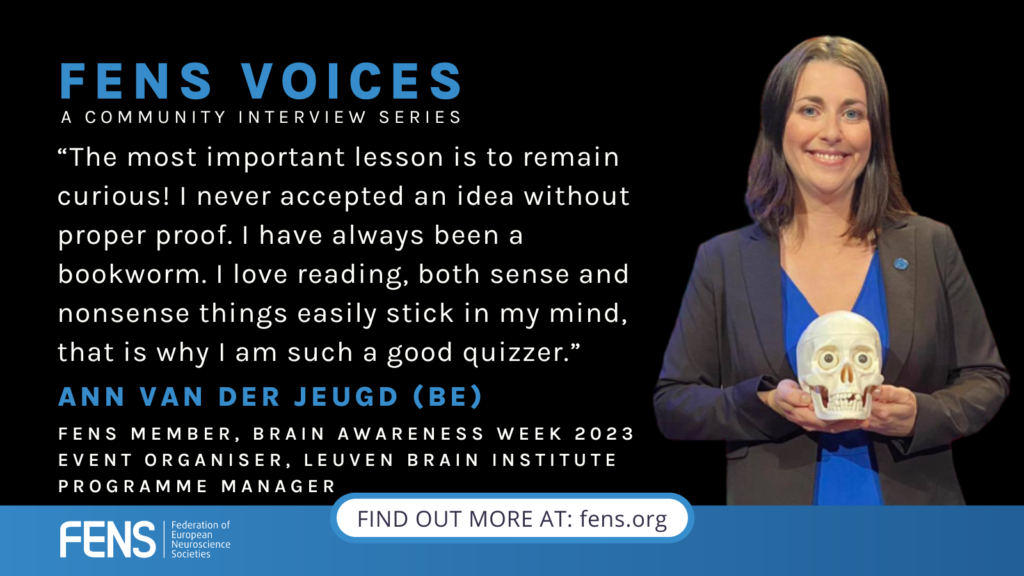

FENS Voices | Ann Van der Jeugd: Always remain curious!

26 May 2023

FENS News, Neuroscience News

FENS Voices caught up with Dr Ann Van der Jeugd, a FENS member and a Brain Awareness Week event organiser from Leuven, Belgium, and the Leuven Brain Institute Programme Manager, helping to unite all neuroscience research at KU Leuven in order to advance our understanding of the brain, both normal and diseased. She is a board member of the Belgian Brain Council, with a personal mission to inform the people about the brain and its disorders, to lobby for an increase of financial and other resources for basic and clinical neuroscience research, and to promote patients’ empowerment in the management of brain disorders and related public health policies. Finally, she is not only a woman working in science, but also a passionate supporter of other women in sciences, as the president of BeWise-Belgian Women in Science, an NPO supporting girls & women in STEM via mentoring and projects, such as GirLS, funded by the Koning Boudewijn Stichting, and WISENIGHT, funded by the European Commission.

When and how did you first hear about brain research? What made you aspire to develop a career in neuroscience?

AVDJ: As a child I was very interested in science, I devoured the books of National Geographic Junior and I always had my nose in books. Encyclopaedias and books about history and the human body in particular also fascinated me enormously. I used a small microscope that I received as a gift for my tenth birthday to examine all of the animals that I could find in our garden. As I got older, I became very interested in psychology and I thought it would be cool to learn all about our behaviour at university, as biological and evolutionary psychology were my favourite subjects. I am therefore very pleased that since last year I have had a column about behaviour in the science magazine EOS Wetenschap, which appears in Belgium and the Netherlands.

What were the highlights of your early academic experience? What was the most important lesson that you learned?

AVDJ: I can say that I am a pioneer student, the first one in my family to go to university. I was not allowed to live in a kot (student flat, in Flemish), so I always commuted 2 hours by train. As I am an only child, my parents did not trust this and also, because I was kind of a rebel, I never studied and I always kept on going to parties all throughout my school career, even during the exams. Nonetheless, I always passed with high distinction so there was not much my parents could say to make me change my routines. The most important lesson is to remain curious! I never accepted an idea without proper proof. I have always been a bookworm. I love reading, both sense and nonsense things easily stick in my mind, that is why I am such a good quizzer. I also thoroughly enjoy what might seem meaningless work to others, like gardening or cleaning. I like to mingle periods of thinking and studying with bouts of mindless activities such as gaming or playing with Lego (I am a sucker for Lego). I feel I need that combo in order to be creative. When I am writing a piece for the EOS magazine, I always go for a walk outside in order to ‘write’ the outline in my head before putting it on paper afterwards.

At the end of my university internship, my promoter asked me to do a PhD in his lab, and frankly I never heard of a doctorate before. I thought only real doctors could do it. But since my marks were great, I got offered a scholarship by the FWO, Flemish Research Fund, and that was it. I managed to get more scholarships from the FWO afterwards, as well as grants allowing me to buy equipment and support which allowed me to attend conferences abroad. The first conference I ever attended was memorable, as I went in 2009 directly to the biggest neuroscience event, the SfN meeting. Also, this was also my first trip outside Europe. The PhD really was my ticket to see the world. After that first conference, I realised I really liked travelling a lot, so I attended and presented at summer schools, winter schools and conferences thanks to the help of FENS. I am really grateful for the opportunities I got from all of these funding bodies. By the end of my PhD, I had 13 publications out of which 10 were as lead author. That was really outstanding, but I did not realise it at that time. I just loved doing lab work and (net)working abroad so it never felt like a job to be honest. I also have to thank someone special here, my first mentor, Dr Tariq Ahmed aka Taz. He taught me how to do electrophysiology in vitro slice recordings and everything about ‘80s music (he grew up in Manchester). We were a great team and had so much fun together. Unfortunately, he passed away some years ago because of a brain tumour, but he really was my science hero.

Both your PhD and your postdoctoral project focused on characterising Alzheimer’s disease mouse models from cellular to behavioural level, on the effects of pharmacological therapies on learning, memory and synaptic plasticity. Why did you choose AD?

AVDJ: Back in 1993, I was enjoying the summer holidays (summers seem endless when you are 12 years old) and I remember our Belgian king suddenly dying of a heart attack in Spain. I’ll never forget how my grandmother cried because of this. It almost felt as if she lost her husband again (my grandfather had passed away some years already). Some years later, when I was 18, my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Sure, I had heard of it, but that was supposed to be a problem related to older people. My grandmother was in her 60s when she was diagnosed. Okay, so she forgot where her keys were or left something behind somewhere. Who hasn’t done that before? The diagnosis didn’t ring true for me for quite some time. She seemed like the same loveable person I had always known. Our sweet grandmother. My mom tried to get me to read literature on Alzheimer’s, but being a typical teenager, I just didn’t want to know. I didn’t want to think about what may be coming. I didn’t want to think about how it might end. The progression was slow at first and then it seemed to worsen steadily. She wouldn’t remember us when we’d come to visit. I know many people have experienced this and I know I’m not alone when I say that it feels like a slap in the face the first time. Every now and then she’d reminisce about something from her youth. It would be something I had never heard before, but then she would grow quiet and not recognise any of us in the room. She is the reason why I choose to study Alzheimer’s disease when I had the opportunity to start a PhD back in 2007. I thought this might be the opportunity to remember my grandmother, that this would be my chance to make up for those teenage years when it was too frightening to learn about AD.

AVDJ: Back in 1993, I was enjoying the summer holidays (summers seem endless when you are 12 years old) and I remember our Belgian king suddenly dying of a heart attack in Spain. I’ll never forget how my grandmother cried because of this. It almost felt as if she lost her husband again (my grandfather had passed away some years already). Some years later, when I was 18, my grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. Sure, I had heard of it, but that was supposed to be a problem related to older people. My grandmother was in her 60s when she was diagnosed. Okay, so she forgot where her keys were or left something behind somewhere. Who hasn’t done that before? The diagnosis didn’t ring true for me for quite some time. She seemed like the same loveable person I had always known. Our sweet grandmother. My mom tried to get me to read literature on Alzheimer’s, but being a typical teenager, I just didn’t want to know. I didn’t want to think about what may be coming. I didn’t want to think about how it might end. The progression was slow at first and then it seemed to worsen steadily. She wouldn’t remember us when we’d come to visit. I know many people have experienced this and I know I’m not alone when I say that it feels like a slap in the face the first time. Every now and then she’d reminisce about something from her youth. It would be something I had never heard before, but then she would grow quiet and not recognise any of us in the room. She is the reason why I choose to study Alzheimer’s disease when I had the opportunity to start a PhD back in 2007. I thought this might be the opportunity to remember my grandmother, that this would be my chance to make up for those teenage years when it was too frightening to learn about AD.

After your PhD, you moved to Australia, where you worked in the Clem-Jones Centre for Aging and Dementia Research at the Queensland Brain Institute, investigating the feasibility of ultrasound mediated Alzheimer vaccination therapy. Were the methods and techniques from the host lab different from what you were used to in Belgium and how was your Australian experience overall?

After your PhD, you moved to Australia, where you worked in the Clem-Jones Centre for Aging and Dementia Research at the Queensland Brain Institute, investigating the feasibility of ultrasound mediated Alzheimer vaccination therapy. Were the methods and techniques from the host lab different from what you were used to in Belgium and how was your Australian experience overall?

AVDJ: At the festive reception following my PhD defense in 2014 one of the jury members, the famous Alzheimer researcher Prof Bart De Strooper, urged me to go abroad and explore the world. Coming from the same hometown as himself (a very rural place), I took his advice and immediately looked for an interesting place on the opposite side of the world: down under. Everything changed, it was the first time I travelled so far and lived abroad. I took my husband and daughter along. She was 1 year old. It was really so much fun, although the lab atmosphere was very different from the one I was used to in Belgium. The PI was not a laid-back Australian, to say the least. We tested a novel technique to get a vaccine inside the brain, first on mice (model of AD), then on sheep (sheep skull resembles a lot the human skull). These were really exciting times, building and testing the novel ultrasound set-up in a small team. I had good colleagues: two awesome lab technicians, four great postdocs, four amazing PhD students, we were a good and well-oiled team. Without going into details, I really worked my ass off (3 papers, of which one in Brain in 1 year is not bad), but it was never enough for the head of the lab who was – in my opinion – micro-managing too much. Also, during the weekends, my husband (who was a stay-at-home dad in Oz in order to take care of our daughter) wanted to explore the country. We started with camping in the nearby surroundings of Brisbane where we lived, and ended up on camping- trips in Cairns, close to the Great Barrier Reef and even in Perth, the other side of Australia. After one year, I was exhausted, and glad to return to Belgium where we had the help and support of our family. But upon returning to Belgium, a streak of bad luck hit our family. Within five months of being back, at first my husband’s father passed away, and a month later my father too. It was really a setback on a personal level. Luckily, I had my daughter Liv, which kept me going. I never used the ultrasound technique again. In fact, I submitted an ERC STG (European Research Council Starting Grant) and got a nice 91.4% but as one knows, the cut-off for life-sciences panels is in the 94’s.

You moved on to San Francisco, as a visiting fellow at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, while working on your research project. What can you tell us about The memory of smell: the role of olfactory (mis)processing in dementia?

You moved on to San Francisco, as a visiting fellow at the UCSF Memory and Aging Center, while working on your research project. What can you tell us about The memory of smell: the role of olfactory (mis)processing in dementia?

AVDJ: When researching the rodent models of amyloid (from De Strooper), tau (from Mandelkow / Buee) and triple (amyloid with tau), I phenotyped all of them behaviorally. The typical Morris Water Maze, but also other hippocampus-dependent tests. That’s how I found out that all of the mice were experiencing olfactory dysfunction early onward in the disease process. It was part of the reason they failed the famous Social Preference / Social Novelty (SPSN) test, where they encounter a stranger mouse. Mice typically get to know each other by exploring each other by sniffing front and bottom. So I started digging into this phenomenon and discovered they did not remember the smell. Reading the literature, I indeed found out that in frontotemporal dementia (which typically starts in the frontotemporal lobes) patients exhibit problems in face recognition and display a lack of disgust (eating spoiled and rotten foods for instance). I wanted to gain experience with humans, after all, I had been doing lab work for over a decade by then and never got to see a patient in real life. I did a clinical internship at the MAC and saw so many inspiring people: tutors, instructors, nurses, doctors, professors, families and patients. It really was an eye-opener: every week we did the rounds where everyone sat together and discussed the diagnosis and treatment in front of the family and the patient. I have so much respect for the patients and families that put their faith and trust in our hands. It really was an honour to be part of this amazing ecosystem and brain valley altogether because I also attended many science fairs from tech companies in Frisco.

What AD-related project are you working on now?

AVDJ: We just published a University Cambridge book, “Dementia and Society”. “We” is my former PI Prof Rudi D’Hooge from my PhD and my new PI Prof geriatric psychiatrist Mathieu Vandenbulcke, who is the editor. It basically combines our preclinical insights with clinical works, so it nicely merges both of my interests.

I also have minor projects up and running, as a coordinator, not as a promotor. For instance, project MenoMouse, which looks at the links between menopause and dementia. I submitted it in 2019 for an MSCA grant (Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions). I got 92%, which was unfortunately not enough. “Only the Lonely” is another project I believe in, which is looking at the effects of social isolation on developing dementia. This project was in full swing during the COVID 19 lockdown. In that context there were not only the mice who got isolated for 3 months, but also people during that horrible period in 2020. In fact, I was interviewed for a TV show (in Dutch) about this project during the lockdown, in May 2020. This also made me think about my work and work-life balance. When I needed to take care of the mice, I could not be at home with my kids, who actually needed home-schooling. That made me feel that I failed (my daughter doubled her first year of primary school), and I decided to quit doing science. Later on, I heard that they were looking for someone enthusiastic to kick-start the Leuven Brain Institute. So, I applied for the first time in my life for a job and got it.

You are currently a Board Member in the Belgian Brain Council and the President of BeWiSe, the Belgian Women in Science, an organisation that is supporting the position of women in science both in academia and industry through mentoring and numerous projects. When did you develop an interest in advocacy?

You are currently a Board Member in the Belgian Brain Council and the President of BeWiSe, the Belgian Women in Science, an organisation that is supporting the position of women in science both in academia and industry through mentoring and numerous projects. When did you develop an interest in advocacy?

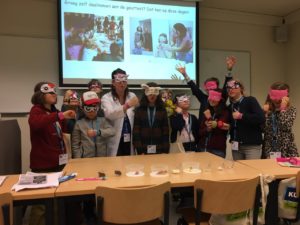

AVDJ: While working in Australia I really needed a mentor. In Oz, everyone had a mentor, it was the American system. So, upon returning to Belgium I looked up mentoring programmes and that’s how I discovered BeWiSe. I became a member and mentee, got an amazing mentor, and became the secretary and attended and organised many events where I met many inspiring people. Three years ago, I was elected as President and now we are organising our third in a row national Women in Science day, and I managed to write an MSCA grant-winning European Researchers’ Night grant, which was our cool WiseNight inclusive science festival in summer 2021. Moreover, BeWise is now the organiser of the Girls leading in Science contest, along with Solvay. A contest in which high school students in the last year can win the first year of university tuition fee! It is really something I enjoy doing, promoting science, and being a role model in a way for young scientists.

Alongside the Belgian Brain Council, we inform and educate the general population about the brain and its disorders, lobby for an increase in financial support and other resources for basic and clinical neuroscience research and promote patients’ empowerment in the management of brain disorders and related public health policies. We are currently carrying out a project Care4Brain promoting Mental Health in Europe under the Erasmus+ programme, and I am a proud organiser of the Brain Awareness Week events in Leuven.

Although your research carried you around the world, you returned to your academic home, back to Leuven, where you are the Programme Manager of the Leuven Brain Institute (LBI). Can you share with us the main goals of LBI and your personal approach to reaching those goals?

Although your research carried you around the world, you returned to your academic home, back to Leuven, where you are the Programme Manager of the Leuven Brain Institute (LBI). Can you share with us the main goals of LBI and your personal approach to reaching those goals?

AVDJ: In parallel with my PhD, I did a lot of science communication, with the aim of feeding our lab’s research back to the general public. I co-organised activities for national science campaigns such as Dag Van de Wetenschap, Battle of the Scientist, and KinderUniversiteit, but also international events such as Pint of Science, SoapBox Science and Brain Awareness Week. In this way, I got to know many scientists from outside the Alzheimer’s research field at KU Leuven who were also involved in brain research. When they were looking for someone to reboot the Leuven Brain Institute in 2020, I didn’t hesitate to take on this challenge. The LBI unites all excellent brain research that is done at KU Leuven and Leuven University Hospitals. With over 140 PIs and 600 young researchers, it forms the beating heart of the neuroscience community in Leuven. I think that every researcher has an interesting story to tell, and I aim to give a voice to our researchers. I believe in giving back, in engagement. Hence, we founded the Scientist meets Patient program, where we pair up scientists with patients, so they can learn from each other. Our commitment extends beyond supporting brain research. LBI wants to actively give back to the community and society and break the barriers and remove taboos surrounding brain conditions.

With our Scientist Meets Patient Program, we want to give researchers the opportunity to gain expertise with patients on a voluntary basis. From person to person: how patients can inspire scientists and vice versa, with respect for both worlds. Finally, creating a sense of belonging is very important to me. People work better in a nice atmosphere, so I am also happy to organise besides our annual science day and meetings of the LBI centres, focus groups and task forces for other events like the Happy Brain Hour, and even performances of our newly established LBI Big Brain Band, composed of PIs and students jamming together. I am a very happy and proud programme manager, and I am looking forward to where this thrilling road will bring me in the future.

About Brain Awareness Week

Brain Awareness Week (BAW) is the global campaign to increase public awareness of the progress and benefits of brain research. Organised by the Dana Foundation, Brain Awareness Week (BAW) is an opportunity to let people know about the progress that is being done in brain research as well as progress in the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disorders of the brain, such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, stroke, schizophrenia and depression. The 2023 edition of Brain Awareness Week took place on 13-19 March. Every year, FENS, on behalf of the Dana Foundation, offers grants to Brain Awareness Week event organisers.

About the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies (FENS)

FENS is a governing partner of the International Brain Bee. Founded in 1998, the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies is the main organisation for neuroscience in Europe. It currently represents 44 national and single-discipline neuroscience societies across 33 European countries and more than 22,000 member scientists. Discover FENS and subscribe to our biweekly News Alert, with information on our latest calls and activities.