FENS Voices | Arish Mudra Rakshasa-Loots: Breaking the barriers

20 October 2023

FENS News, Neuroscience News, Society & Partner News

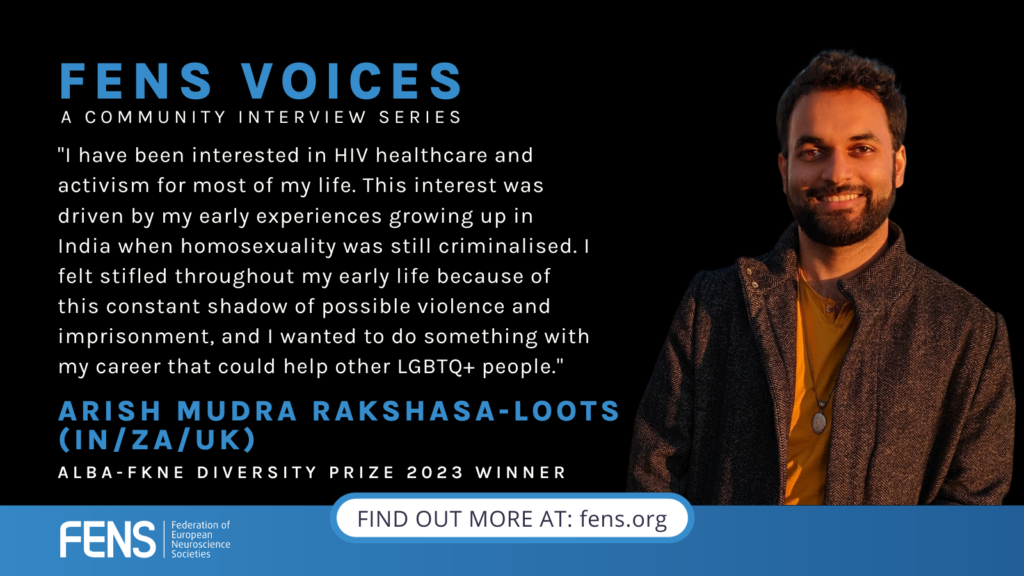

FENS Voices was delighted to catch up with Arish Mudra Rakshasa-Loots, the winner of the ALBA-FKNE Diversity Prize 2023, about his work toward reducing HIV-related healthcare inequities and promoting gender, ethnic and regional diversity in mental healthcare, research and teaching. Arish is a neuroscientist, educator, and activist. He is currently completing a PhD in Translational Neuroscience, funded by the Wellcome Trust. Arish is primarily interested in how neuroscience can help address the prevalence of mental health issues amongst people living with HIV. Arish holds a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, through which he worked with grassroots HIV/AIDS movements around the world, and a BA in Liberal Arts from Earlham College (USA), where he studied Biochemistry, Neuroscience, and Ancient & Classical Studies. He aspires to train the next generation of conscientious scientists in neuroscience and global health. Read the full interview below.

What were your main hobbies while growing up?

What were your main hobbies while growing up?

AMRL: I haven’t been asked this in quite a while! Like most self-professed nerds, I think reading was one of my favourite pastimes. I quite enjoyed the Lord of the Rings series, which was a big part of how I learnt the English language, and the Harry Potter series, though that love is now marred by the author’s relentless transphobia.

You identify as a queer brown immigrant and you are committed to creating an inclusive culture in science. Did you ever feel different or excluded? If so, how did this impact your studies?

AMRL: Absolutely – I think any of us who exist in any way in the margins of society experience some form of “othering”. For those of us who are multiply minoritised, this experience is amped up by several degrees. I think the greatest direct impact on my work has been because of my identity as an immigrant. There are many substantial hurdles that I face because of visa restrictions that limit what I can do. For someone whose research is intentionally cross-cultural, this makes life quite difficult at regular intervals. Travelling to set up a study or run some analyses is not as simple as getting on a plane. For me, it often involves months and months of preparations (and rejections, and re-applications) for visas. Visa restrictions have also often limited my career trajectory and funding or work opportunities available to me. After my PhD, for example, I want to train as a clinical psychologist to be able to offer clinical support to the people living with depression whom I interact with in my research, but in most countries this training is restricted to those who are citizens or permanent residents, so I am barred from even applying for these training programmes.

How did you get in touch with brain research?

AMRL: My introduction to brain research came from the incredibly supportive Prof. Michelle Tong, then at Earlham College. I had a long-standing passion for HIV research which I had taken with me to Earlham, with a vision to eventually do research in HIV immunology, but I had decided to stay open to a diversity of research experiences during my training. I happened to spend a semester doing behavioural neuroscience research in Prof. Tong’s lab, where we worked on characterising the biological underpinnings of olfactory memory consolidation in mice. My time in this lab showed me that I really enjoyed the translational capacity of neuroscience research, but also the emphasis on rigorous methodology and statistics to study phenomena that can often be quite abstract. Prof. Tong is also just an all-around cool human being, which featured heavily in my decision to continue in her lab for my undergraduate thesis project, which we eventually went on to publish. I knew I wanted to continue doing HIV-related research, but at that point I switched from immunology to neuroscience, because of how open, collaborative, and friendly I found brain researchers to be.

How did it feel to study both science and arts and which was your favourite course during college and why?

AMRL: I went to the US for undergrad specifically because I wanted a liberal arts education, and I am so happy that I made that decision. I think – and I am definitely biased here! – that liberal arts is an exceptional education system which trains you not to specialise in something really complicated and niche, but to ask critical questions and develop a curiosity and versatility to learn (almost) anything. I am so glad I had that experience!

It’s hard to pick favourite courses, but if I absolutely had to, I would say that two courses that I really enjoyed were Reading Ancient Greek, because we got to read a novel written over 2000 years ago in its original language, almost as if Xenophon was crossing the millennia to tell us a story himself, and London: City of Art, a course in which we spent time in museums and galleries across London to question how each institution chooses to portray its history and its collections and whose perspectives are missing from these narratives.

As you have majored in Biochemistry and Neuroscience and minored in Ancient & Classical Studies during your BA in Liberal Arts at Earlham College (US), you benefited from a broad training, which led you to have several academic interests, ranging from computational biophysics to postcolonialism. During the Renaissance, science blended with humanities. Leonardo da Vinci, Leon Battista Alberti, Johannes Kepler and Sir Isaac Newton all thrived across several areas. Afterwards, research fields became more strictly divided. How do you feel about the ongoing separation of science and humanities?

As you have majored in Biochemistry and Neuroscience and minored in Ancient & Classical Studies during your BA in Liberal Arts at Earlham College (US), you benefited from a broad training, which led you to have several academic interests, ranging from computational biophysics to postcolonialism. During the Renaissance, science blended with humanities. Leonardo da Vinci, Leon Battista Alberti, Johannes Kepler and Sir Isaac Newton all thrived across several areas. Afterwards, research fields became more strictly divided. How do you feel about the ongoing separation of science and humanities?

AMRL: I think this separation is quite artificial, but the way that we have set up academia today is one that enforces it quite strictly. The core of research – asking critical questions and developing ways of answering them – remains the same regardless of whether you’re carrying out research in neuroscience or ancient history; it’s the methodology to answer those questions that varies. I am swimming against the tide here, but I continue to use my training as a liberal arts scholar to carry out and publish research in the humanities and social sciences, in addition to my neuroscience research. It’s certainly got its advantages – for one, I think being able to look beyond disciplinary silos allows for more creativity. It gives us more opportunity to look at something with fresh eyes and ask, “how might I take this knowledge from this field, and apply it to this other field? and what might I discover if I do?” I do feel sometimes that being a generalist in a profession designed for specialists puts me at a practical disadvantage, but I still really enjoy being able to move across disciplines and following my curiosity wherever it may lead me.

Your current research asks whether neuroinflammation arising from HIV infection in the brain contributes to the high risk for depression among people living with HIV. How did you end up following this topic and what is your approach?

AMRL: I previously held a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, which selects a few graduating students from across the US each year and gives them the freedom and resources to travel globally in pursuit of their passion. I chose to spend my Watson Year working with people involved in disrupting the HIV pandemic in many different countries and on many different scales, ranging from UNAIDS to an NGO that someone ran out of a flat in Malta. At one point during this year, I attended a meeting in Barcelona on “living with HIV”, where several people pointed out that managing mental health issues is one of the next big frontiers in HIV research. That’s how I ended up working in the field of HIV mental health. My research tries to put together what we’ve learned in psychiatry over the last two decades, which is that inflammation seems to be linked to depression for at least some people, and in HIV research, which is that people living with HIV experience inflammation despite successful antiretroviral therapy. So the question I found myself asking was: could it be that people living with HIV are at greater risk for depression because they experience greater inflammation? There is, of course, also a substantial contribution by factors like housing or food insecurity, discrimination and stigma, but I am trying to determine whether there is a significant neurobiological contribution to this risk as well.

When and how did you become active in initiatives aiming to eradicate HIV/AIDS?

AMRL: I have been interested in HIV healthcare and activism for most of my life. This interest was driven by my early experiences growing up in India when homosexuality was still criminalised. I felt stifled throughout my early life because of this constant shadow of possible violence and imprisonment, and I wanted to do something with my career that could help other LGBTQ+ people. Having also found an early interest in the natural sciences, I discovered that HIV healthcare was a clear and impactful area where LGBTQ+ rights activism intersected with biomedical research. I’ve been working towards a career in HIV-related research ever since.

You received the ALBA-FKNE Diversity Prize 2023 for being a vocal advocate of equity and inclusion in neuroscience, for your awareness of modern systemic inequalities. What does this award mean to you?

AMRL: This award has been so encouraging. Often the work that we do to promote equity and inclusion within our “day jobs” can get overlooked, and for someone who struggles against multiple systemic barriers everyday, I do sometimes get to a point where I am drained of all energy. But an award such as this encourages me to keep going, and to keep working hard to dismantle those barriers that I am facing, so that others who come after me can go even further than I will.

Given your wide academic training, what do you plan to focus on in the following years? What is your dream research project?

AMRL: As I mentioned briefly before, my hope is that I will get to train as a clinical psychologist, so that I can combine my research and clinical training to support people living with HIV who experience mental health issues. I also want to work closely with NGOs in ensuring equitable access to mental health services, especially in formerly-colonised nations. I don’t have a dream research project, because – and I’m sure I’ll shock some people when I say this! – in my view, research is a means to an end. It’s not necessarily something I dream about. Rather, it’s a way for me to train others, build capacity in the Global South, and facilitate the translation of scientific knowledge into accessible interventions. In the long term, I particularly want to work with others towards developing a scalable and stratified multilevel model of support, involving biological, psychosocial, and socioeconomic interventions, to help reduce the risk for depression in people living with HIV.