FENS Voices | Alisha Vabba: Bridging domains

03 February 2023

FENS News, Neuroscience News

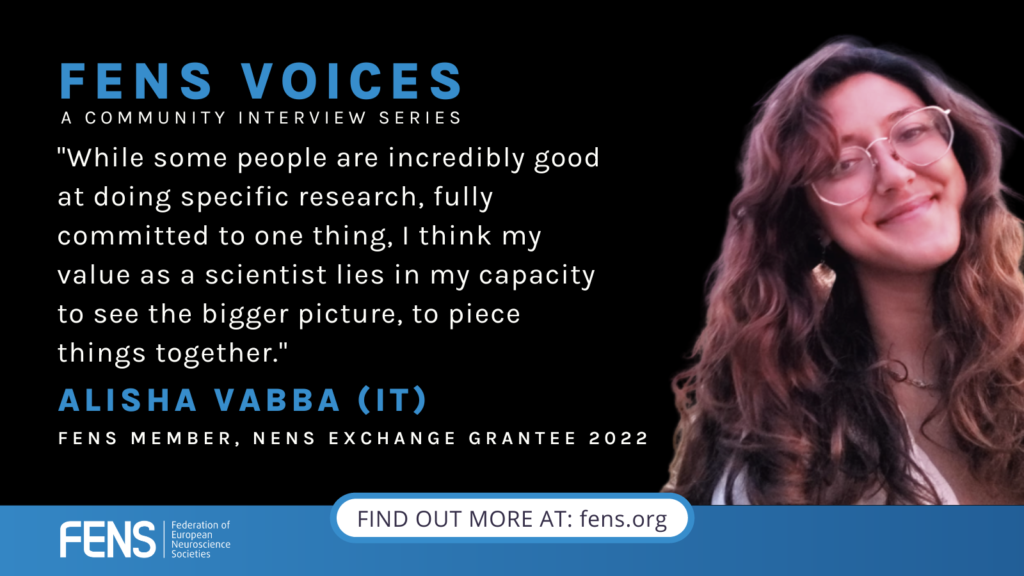

This week FENS interviewed Dr Alisha Vabba to find out more about her research and the impact of the NENS grant that she received in 2021. Currently, Alisha is a postdoctoral researcher at the Italian Institute of Technology, where she investigates the role of the body in moral behaviour, using a combination of physiological recording and stimulation methods. In the near future, she hopes to gain more experience in using immersive virtual reality as an experimental means to induce bodily illusions and recreate complex social scenarios.

What got you interested in social decision-making?

AV: Having an educational background in the social sciences and philosophy, I started my research career in social neuroscience with a strong interest in how our corporeal representations shape our self-awareness and ultimately determine social cognition and behaviour. According to theories of embodied cognition, our experience of the world is grounded in our bodies. We experience everything through our bodies and how our bodies physiologically react to external environmental situations. Our feelings and emotions, our well-being, our social interactions, and decision-making process are all guided by bodily sensations. Thus, understanding how our bodies work and our awareness of these processes can be a fundamental tool to not only study, but that can influence human social behaviour. My greatest ambition as a researcher is to be at the forefront of social progress and to conduct research that has a high impact on policy making. For example, by working towards improving altruism, empathy, and pro-sociality.

Working on a doctoral thesis while doing lab research can be a very complicated process, with a lot of ups and downs. What moments proved to be the most difficult? What were the challenges of being a PhD student and how have you overcome them?

AV: This is a hard question to answer, as I completed my PhD while a pandemic was in full swing, but I guess that’s part of the package. I think what you learn during your PhD is that as a researcher, as a scientist, you need to be flexible and adapt to the times: things change, paradigms shift, you spend months or even years working to prove something only to realise you were wrong. It’s important to remember your work is part of a bigger picture, and to not lose touch with the final purpose of your research and with what’s going on outside your little circle and specific objectives. It is hard sometimes, because it’s easy to get lost in the workload and deadlines. Things start accumulating, you’re testing, submitting papers, writing grants and reports, running analysis, learning, booking rooms and then, to top it off, equipment keeps breaking. When you start a PhD, this escalation of problems can be a bit of a shock. It gets easier with time, as you learn to handle the workload and remember to always take a step back and clear your mind. Conferences and friendly “science sharing” help a lot, and the lack thereof during the pandemic really made me realise their importance.

Who is your role model in science and what makes this person special?

AV: I just read the biographical book of Kary Mullis, the biochemist who won the Nobel prize for discovering PCR. I found him fascinating, not so much for his somewhat controversial ideas, but because he was so human and relatable. He made an incredible discovery that revolutionised DNA research and yet he was far from being a perfect, rigorous human being, instead showcasing creative, eclectic, and sometimes bizarre ideas and interests (such as aliens, astrology and he was even a surfer, just like me). I want my life to be filled with different passions and I love how science can mix and match with other domains. I let my day-to-day life inspire my science and vice versa. For example, there are many references to the human body in my poetry. While some people are incredibly good at doing specific research, fully committed to one thing, I think my value as a scientist lies in my capacity to see the bigger picture, to piece things together. This might be tied to my diverse background in statistics, philosophy and politics, psychology and neuroscience. I think both types are important in science. In general, I find role models in people who speak up for themselves and are not afraid to ask what they feel is right. I really struggle with hierarchies and status quos, with people accepting things as they are because that’s how it’s always been. I value respect, honesty, and flexibility a lot.

You are a NENS Exchange Grant awardee. How has it impacted your career? How important are these types of grants for PhD students?

You are a NENS Exchange Grant awardee. How has it impacted your career? How important are these types of grants for PhD students?

AV: The chance for a visiting period abroad was so important for me and I was really grateful it was possible during the pandemic. Being able to travel and experience different realities and mindsets, and learning to adapt to them is a key skill for a young researcher. It teaches you a lot about what you want and do not want to achieve in your career, what can be changed, which qualities you value and, of course, it keeps you open and updated. I’ve already stressed enough how much I value stepping out to see the bigger picture and nothing helps you do that better than experiencing different realities. Brighton really influenced my post-PhD decisions, as I really enjoyed working with virtual reality and appreciated what a valuable tool it can be to manipulate body awareness. I also learned new skills in physiological recording and vagus nerve stimulation, which I am now using in my postdoctoral research and which have been incredibly useful for both me and my home laboratory. None of this would have been possible without the NENS Exchange Grants, so I am incredibly grateful for the support I received.

What do you want to do after your postdoc?

AV: I’ve applied for a European grant with a project at a lab I’m very excited about. I want to further develop my skills in virtual reality programming and 360 filmmaking, for the illusory recreation of social scenarios and to transform the self. Research shows how virtual reality (VR) can be used to induce the perceptual illusion of ownership over a virtual body, even when it is drastically different in size, skin tone, age, and gender, leading to important changes in perception, empathy, and behaviour. For example: embodying a dark-skinned avatar reduces implicit racial bias in light-skinned people, embodying a female victim of domestic violence improves emotional recognition capacities in gender violence offenders, and even embodying Einstein can increase performance in cognitive tasks, particularly for people with low self-esteem. Furthermore, VR allows us to replicate ecological social experiences in an experimentally controlled environment, and to investigate scenarios that are complex or unethical to recreate, such as violent behaviour. Thus, I wish to combine this technique with my expertise in psychophysiology, to study how we experience the social world through our bodies, and “putting yourself in someone’s shoes”, to encourage empathy and a change in attitude.

About NENS Exchange grants and FENS/IBRO-PERC Exchange Fellowships

The NENS Exchange Grants have been replaced by the new FENS/IBRO-PERC Exchange Fellowships. Directed at PhD students and early post-doctoral fellows located in Europe, the FENS/IBRO-PERC Exchange Fellowships Programme aims to foster and broaden the scope of their methodological training by supporting goal-directed laboratory visits in established European laboratories. Find out more about.

About the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies (FENS)

FENS is a governing partner of the International Brain Bee. Founded in 1998, the Federation of European Neuroscience Societies is the main organisation for neuroscience in Europe. It currently represents 44 national and single-discipline neuroscience societies across 33 European countries and more than 22,000 member scientists. Discover FENS and subscribe to our biweekly News Alert, with information on our latest calls and activities.