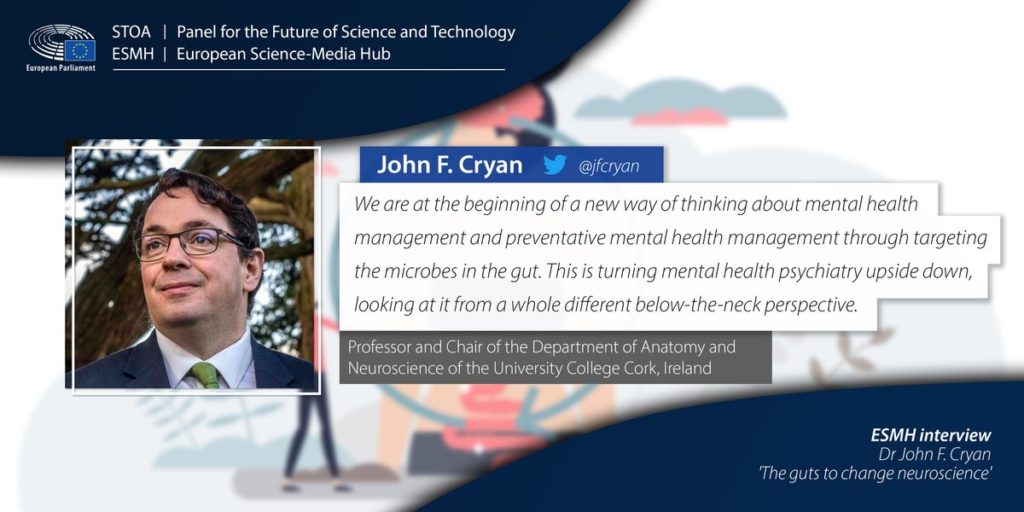

Interview with Dr John Cryan: ‘The guts to change neuroscience’ with the European Science-Media Hub

10 May 2023

FENS News

We are excited to share the interview “The guts to change neuroscience’ by FENS member Dr John Cryan, recently published in EP’s Science Media Hub.

Find out how mice have allowed him to discover the influence that the microbiome has on the development of the brain.

Your work gravitates around the interaction between the brain, gut and microbiome (the microorganisms in a particular environment). What is the tie between them?

John Cryan: As I work in the neuroscience department of a medical school, I know from experience that in medicine we tend to compartmentalise the body; neuroscientists are trained to predominantly focus on what happens above the neck.

The work that we do now, which is looking at signals between the gut and the brain, disrupts that, and people may think it is totally new.

Nonetheless, Hippocrates already stated: “All disease begins in the gut”. And people researching areas such as satiety (the satisfied feeling of being full after eating) have been working on gut-brain signalling for hundreds of years already. But what is new is the understanding that the gut-brain signalling could also be relevant to a variety of other brain-related conditions, also in terms of modulating (altering or stimulating) the brain in different ways.

Understanding how our brain is constantly receiving signals through our gut is of great importance. These are sent and received through a variety of ways. What is quite new as well is that we realised in the last two decades that the microbiome in the gut is really important for gut-brain signalling as it is for all aspects of our physiology. So, understanding that we now have a microbiome gut-brain axis has been one of the hallmarks of my research.

The gut-brain signalling occurs through direct neurolinks: we have nerves, most notably the vagus nerve (the longest nerve of the autonomic nervous system in the human body), that send signals from the gut to the brain. We also have our enteric nervous system, which is also often referred to as “our second brain”. The enteric nervous system is really important for maintaining homeostasis in the gut, for digestion, for motility and other functions. But it also is a very important part of our signalling to the brain.

What is often forgotten, even by neuroscientists, is that there are more nerve cells in our gut than there are in our spinal cord. We also know that the microbes in the gut are similar to little factories producing various weird and wonderful chemicals that our bodies wouldn’t make otherwise. And factories are dependent on the quality of the workers and the raw materials which come from one’s diet.

Why is the communication between the gut and the brain important for the body?

John Cryan: This communication is really important for what we call interoception. Interoception sounds like a Christopher Nolan movie, but it actually reflects how we feel and how our internal systems communicate with our brain to sense how we are doing. Gut signals are very much part of that interoceptive process.

Next to informing us about our satiation – if we’re full or hungry, and survival mechanisms around that – gut signals tell us if we’re feeling bloated or if we’re feeling dysphoria, which will be communicated through these visceral signals. We can know if there are pain processes, if we have abdominal pain or other discomfort, or if we have immunological problems.

However, we need to frame microbiome signals from an evolutionary perspective, and really understand that the microbes were there first. We do not have microbes communicating to the brain all of a sudden, but rather the brain has evolved in the presence of microbial signals.

We’re slowly discovering what they are – under baseline normal conditions – and how they are influencing core circuits in the brain, driving and shaping our behaviour.